DE BALNEIS PUTEOLANIS

Ms. 1474

Angelica Library

Dated: 1258-1266

Author: Peter of Eboli

Folio measurements: 184×130 mm.

Genre: Poem

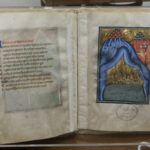

Miniatures: Present.

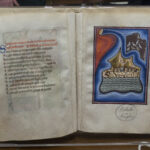

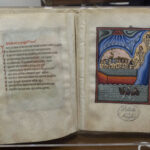

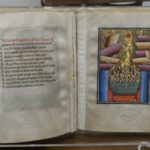

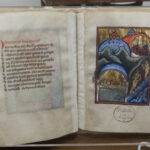

The De Balneis Puteolanis, which is a poem in Latin that celebrates the therapeutic properties of the ruined Baths of Pozzuoli and Baia, was composed around the middle of the 13th century. The author was Pietro da Eboli, a poet who was active at the Norman court and then later, at the Swabian court and who, according to tradition, dedicated the poem to Emperor Frederick II of Swabia. Though the original work was soon lost, it enjoyed considerable fortune and many copies were made as time passed. This copy, found in the Angelica Library is the oldest known, commissioned perhaps by Frederick II’s son, Manfred, to honour his father. And this one is also the most precious because of its miniatures, so full of stories…. And of gold. They are the work of a mid-12th century Neapolitan atelier.

- History and Context

- Structure and Writing

- Iconography and Iconology

- Materials and Execution Techniques

- Censure and Modifications

- Preservation and Restoration

- Bibliography

This 1474 Manuscript, held in the Angelica Library is the oldest testimonial to De Balneis Puteolanis, a poem composed by Pietro da Eboli describing the Baths of Pozzuoli and Baia and celebrating their therapeutic properties. The fame of the Campi Flegrei spa, by then in ruins and nearly forgotten, as the poet regretfully reports, had been widely endorsed since antiquity.

The dating of Pietro da Eboli’s work has proven to be controversial. According to a nearly unanimous opinion among critics, this work is said to have been composed between 1211 and 1221 and dedicated to Frederick II. However, in some very recent studies a proposal has been made that it should be backdated to the period from 1194/5 to 1197, and there has been some speculation that instead of being dedicated to Frederick II it was meant for the latter’s father, Henry VI.

These different suppositions on dating the work and on the identity of its addressee arose first of all from the controversial identification of the historical figures celebrated in the dedication, which can be read in the copy in the Angelica Library on f. 19v.

Though the original manuscript has been lost, given its popularity, many copies were nevertheless made over time. The copy of De Balneis preserved at the Angelica Library is the oldest known copy, and the most valuable, as well, because of its miniatures. Although its date is not entirely certain, it can probably be dated from the age of Manfred, son of Frederick II, who commissioned it to honour his father. Therefore, this copy should be attributed to the years of Manfred’s reign (1258-1266).

However, there are even some rare proposals for attributing it to later date, towards the end of the 13th century, if not surprisingly sometime within the earliest years of the next century.

The De Balneis Puteolanis enjoyed considerable publishing success between the 13th and 15th centuries, in southern Italy and, in especially, in the Campania region. The work is represented by 28 manuscripts, 13 of which are illuminated, by two vernacularisations, one in Neapolitan and one in French octosyllables, and by several printed editions, with the first having been prepared in Naples in 1475 by Francesco Griffolini da Arezzo.

The author of De Balneis Puteolanis was Pietro da Eboli, scholar and poet at the Norman court, who passed into the service of the Swabian court with the accession to the throne of Henry VI, whose fervent supporter he became. There is no certain information on the author’s identity, as many doubts and grey areas still persist, starting with his marital status.

Pietro da Eboli has been portrayed in the famous dedication scene of his first work, the Liber ad honorem Augusti (also known as De Rebus siculis carmen or Carmen de motibus Siculis), whose only surviving copy is being kept in Berne (Burgerbibliothek, codex 120 II, f. 139r). The poet, his head tonsured, is kneeling at the feet of Emperor Henry VI as he presents his book to him, in the presence of the Chancellor and Imperial Legate Corrado of Querfurt. And it is the very same author who states, in the dedication verses of De Balneis Puteolanis, that he had written another encomiastic work for the Swabian court, in addition to the two surviving ones, dedicated to the admirable deeds of Frederick (Frederick II according to some scholars or Henry VI’s father, Frederick Barbarossa, according to others).

The full-page miniatures of the De Balneis Puteolanis in the Angelica Library show close linguistic affinities with the ornamentation in a group of luxury manuscripts traditionally traced back to a lay workshop of artists active in Naples between 1250 and 1260. On a substratum of a clear Byzantine matrix, the miniaturist has grafted a more up-to-date inflection of a transalpine derivation, already used in Frederick’s epoch, and suggestions of classical taste. The result is a commixture of accents, and a vivid cultural polyphony.

Some critics link the commissioning of the manuscript to Manfred (1232?-1266), the illegitimate son of Frederick II and the Piedmont native Bianca Lancia d’Agliano, who, between 10 and 11 August 1258, proclaimed himself king of Sicily (see answer 5). Manfred, who lived at court from childhood and like his father was passionate about science, mathematics, astrology and philosophy, was the last Swabian ruler of southern Italy.

Manfred gave impetus to the production of illuminated manuscripts and more generally to publishing, including copying and re-editing scientific works, and translating scientific treatises from Greek, Arabic and Hebrew. To Manfred’s patronage, among other things, we owe the oldest copy of De Arte venandi cum avibus, the famous treatise by Frederick, transcribed from the Vat. Pal. lat. 1071, one of the most famous illuminated manuscripts from the Swabian period.

Any connection to Manfred with the angelic copy of De Balneis Puteolanis can be excluded, if one accepts the supposition that the manuscript could be dated during the Angevin age and shifts it to the end of the 13th century.

In all probability, the work was composed to be dedicated and donated to the Swabian court.

Informazioni mancanti

This codex is one of the best-known and most sumptuous illustrated manuscripts of the Swabian period, most likely produced at the behest of Manfred. It is part of that corpus of “profane” codices, which were packaged as actual “picture books” destined for sovereigns or the court entourage. Therefore, the codex is an extraordinary testimony of Swabian publishing that has received much scholarly attention.

Almost nothing is known about the history of the codex until 1854, when it was seen in a library by L. Bethmann. A handwritten note on possession on f. 1r (Marij Guidarelli) could be in remembrance of one of the owners.

Latin

The original De Balneis Puteolanis was composed of a series of epigrams whose original number and order have been difficult to determine, due to the work’s continuous revisions, manipulations and evolutions over time.

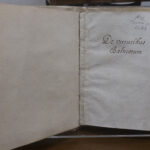

The copy in the Angelica Library is currently composed of 18 epigrams dedicated to the Baths, to which a prologue and dedication are to be added. Tampering and restoration have profoundly changed this copy’s original appearance. It has many gaps and the arrangement of the folios has been altered by a seemingly arbitrary recomposition.

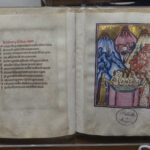

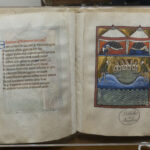

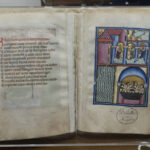

At this time, the folios are glued on compensation waste sheets made of very light parchment. This alteration has led in some cases to an inconsistency between text and image, compromising the complementarity of the two composers. See for example facing folios 9v-10r, where the composition dedicated to the De Prato spa has been juxtaposed with the image of the Tripergula spa.

The ruling was inserted dry.

The text was transcribed by a single copyist using a large-form Gothic rotunda script.

One of the elements supporting the dating of the manuscript to Manfred’s years is the signature of the scribe, Johensis, handwritten at the end of the dedication verses. On f. 19v, the very same copyist who signed two splendid illuminated Bibles, the Vat. lat. 36 held at the Vatican Apostolic Library (known as Manfred’s Bible) and the MS lat. 40 held at the National Library of France. In addition to the scribe’s name, the long colophon of the Vatican copy includes the dedication to Manfred, remembered as princeps (Latin: “first one,” or “leader”). This circumstance allows us to date the volume between 1250 (year in which Manfred was invested with the principality of Taranto) and 1258 (year in which he assumed the crown of the Kingdom).

Not necessarily sequential. The original facies of the poem, its textual sequence, is very difficult to determine due to the loss of some folios, a seemingly arbitrary rearrangement, the alteration of the original structure and numerous variants in the textual tradition of the poem.

Some scholars believe it to be highly probable that from the outset the text of the De Balneis Puteolanis by Pietro da Eboli was accompanied by images that offered a figurative account of the epigrams on the Campi Flegrei Spa, according to the Bildercodex tradition, although the text lacks explicit references to the presence of illustrations, contrary to the Liber ad Honorem Augusti, also by the same Pietro da Eboli. In any case, there is proof of the existence of an archetype, most likely figurative, as early as Frederick II’s time, from which the manuscript in the Angelica Library could have been derived.

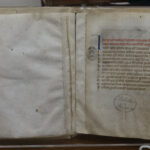

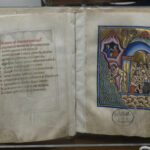

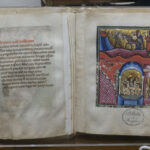

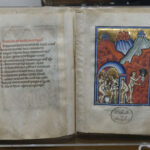

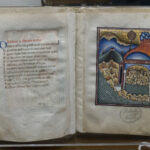

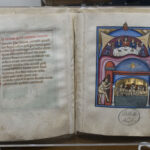

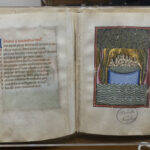

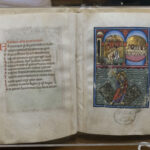

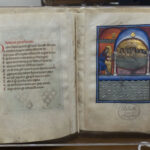

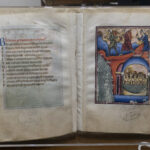

The De Balneis Puteolanis from the Angelica Library is a beautifully illuminated codex. Each composition, in its description and celebration of the virtues of the Spa, written on the verso of the folio, and followed by a full-page illustration on the recto of the next folio, in a verse-and-image layout. The figurative narrative does not merely transpose the text into a figurative illustration but enriches it with narrative, realistic and descriptive details as well as topographical references, perhaps also thanks to knowledge, either direct or mediated by literary works, of the places and themes described.

The intention of author of the poem, taken from the manuscript in the Angelica Library, was to celebrate the therapeutic virtues of the Campi Flegrei thermal waters.

The main personalities of the era who can be associated with this manuscript are Henry VI, Frederick II, Manfred, and Johensis.

The canonical procedure generally followed for writing was as follows:

- The support was selected and prepared, in the case of the De Balneis in parchment.

- The quires were constructed (4, 5 or 6 leaves folded and tucked inside each other).

- The preparatory perforation was carried out.

- The ruling was then inserted, either dry or with coloured lead, according to a full-page or 2-column scheme. The De Balneis has a full-page scheme; the ruling was inserted dry.

- The work was copied, leaving space for initials and headings (i.e. accessory texts such as titles, contents, and the explicit).

- The parts in red were then inserted, i.e. the headings and any pen strokes on the capital letters (it was almost always the copyist himself who would do this).

- The miniaturist would draw in the initials, which could also extend into the margins.

- The illustrations could have been inserted into the spaces specifically reserved for the script. Or, if they occupied an entire page, this could be part of the quire, or the illustration could be executed on a single folio that was then inserted inside the quire. In this second case, when observing the structure of the quire, one would notice an oversized folio with half missing.

- Last, the quires were first sewn together and then sewn onto to the cover. This operation could have also taken place over a period of time.

In the case of the De Balneis, the original structure was altered as indicated above.

The canonical procedure for the execution of a miniature prescribes that on the parchment that has been well-stretched and cleaned, the preparation would be laid out and the basic preparatory drawing would be made.

When preparing the gilding, investigations revealed no presence of Armenian clay, also called ‘bole’, which, instead was very commonly used. Very fine gold leaves would then be applied to the preparation. The gold leaf would then be burnished with agate stone until the gold was gleaming. Gilding could also be applied with a brush. Both techniques were used on the De Balneis. Then finally, the colours with which the backgrounds and figures were to be painted would be prepared. The miniature would first be left to dry and in the end it would be transferred to the person who was to assemble the quire.

One of the relevant features is the extensive use of gold in the full-page miniatures accompanying the epigrams, thus creating a luxury edition of the poem. The gold appears, having been applied in leaf and in powdered form with a brush.

The structure of the volume had been profoundly altered over the course of time and numerous folios have been lost. The current sequence of quires does not respect the original, whose hypothetical reconstruction would be extremely difficult.

The manuscript appears to have been restored over time, as can be seen, among other things, from the compensation waste sheets and the presence of animal glue on folio 13. Unfortunately, it is not possible to recover any documentation on the codex restoration.

Sampling with a sterile swab was carried out on the cover and on some folios of the manuscript. Few microbial contaminants, which were taxonomically identified using Sanger and Next Generation Sequencing techniques, were grown from the samples.

Within the scope of the Codex 4D project, chemical surveys were conducted using the high-performance liquid chromatography HPLC and microbiological investigations using Sanger and Next Generation Sequencing. Thermographic and reflectographic analyses were also conducted in the mid-IR (3-5 µm spectral range). These are imaging techniques that allow structural and/or subsurface elements of both the ligatures and the miniatures to be visualised.

In addition, UV, hyperspectral, XRF and RAMAN fluorescence analyses were conducted on the miniature on folio 13r, enabling the identification of materials and pigments and their stratigraphic location. The results of these investigations are included in the contextualised annotations on the virtual model explorable through the Codex4D section.

A small number of contaminants were able to grow from the samples on which microbiological analyses with Sanger sequencing were conducted. These were microorganisms brought about by handling by users or found in the air of the Library, also because the volume is in an excellent state of preservation.

The HPLC chemical analyses revealed a sub-optimal state of preservation of the paper support and traces of animal origin glue.

Reflectographs in the mid-IR were mainly used to align RGB images with thermographic images so that a 3D representation in the IR could be created. Thermography was used to study some of the miniatures. This method revealed some useful information on the state of adhesion of the gilding (no sub-surface detachments extending from the small gaps were visible on folio 13r, while some detachments were found in the upper portion of the miniature on folio 10r. Both methods showed some elements of the preparatory drawing with greater contrast. Thermographic surveys carried out on folio 10r revealed a small pentimento that would appear to consist of the depiction of a jellyfish, which was never executed in the pictorial layer.

UV, hyperspectral, XRF and RAMAN fluorescence surveys conducted on ff. 9v-10r and especially ff. 12v-13r, made it possible to identify the constituent materials and their behaviour when exposed to different light frequencies, especially the pigments, and their location.

The precise results of all these surveys have been included in the contextualised annotations on the virtual model, which can be explored through the Codex 4D section.

For the extensive bibliography on the manuscript, see: https://manus.iccu.sbn.it/risultati-ricerca-manoscritti/-/manus-search/cnmd/102297?

Also see at least the most recent:

- MADDALO, Il De Balneis Puteolanis di Pietro da Eboli. Realtà e simboli nella tradizione figurativa, Città del Vaticano 2003.

Pietro da Eboli, De Euboicis aquis. Critical edition, translation and commentary by T. DE ANGELIS, Firenze 20018.