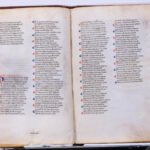

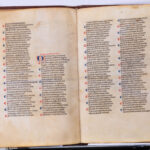

Divine Comedy

Ms. 1102

Angelica Library

Dated: 1325-1350

Author: Dante Alighieri

Folio measurements: 235×160 mm.

Genre: Poem

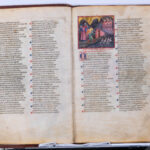

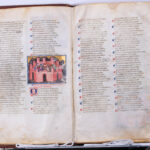

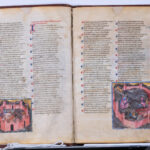

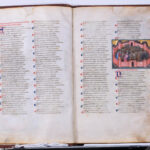

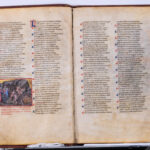

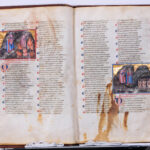

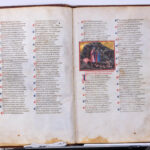

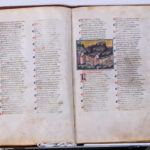

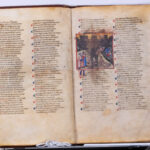

Miniatures: Present in the Inferno

Manuscript 1102 of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy was produced in the Emilia area, between 1351 and 1400, thus shortly after the poet’s death. The parchment folios measure 345 x 240 mm. The manuscript tradition of the Divine Comedy is very rich, whilst the codex held at the Angelica Library is one of the oldest and most precious examples of Dante’s epic poem.

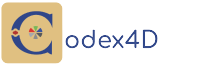

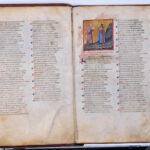

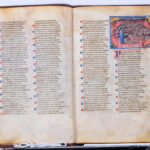

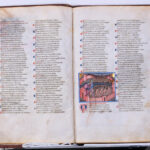

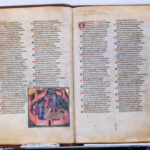

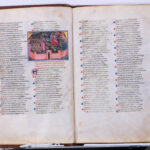

The rich iconographic programme originally provided for 100 miniatures, one for each canto of the poem, to introduce its opening. However, only the 34 miniatures of the Inferno were realised, and only the blank spaces intended to house the others remain.

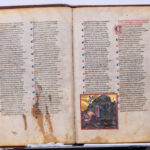

There are quite a few abrasions and censored portions in the illuminated images, especially on the nudity of the devils, perhaps added by a particularly devout owner. Stains generated by past biodeteriogenic agents can be seen on many folios.

- History and Context

- Structure and Writing

- Iconography and Iconology

- Materials and Execution Techniques

- Censure and Modifications

- Preservation and Restoration

- Bibliography

The manuscript contains the entire text of the Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri (ff. 1r-90v.) and, in in the closing, as a commentary on the poem, there are chapters by Jacopo Alighieri (Dante’s son) and Bosone da Gubbio, inscribed by the same hand that transcribed the text of the Divine Comedy (ff. 90v-92v). Only sometime later, probably in the 15th century, were some verses from the Alexandreis by Gautier de Chatillon added (f. 93r).

The manuscript’s dating, estimated to range between 1325 and the early 1400s, has been controversial and is still being debated today.

The manuscript tradition of the Divine Comedy is very rich. The codex held at the Angelica Library is one of the oldest and most precious examples of Dante’s epic poem.

The commissioner of the manuscript has not yet been identified. Nevertheless, judging by its preciousness, it was most likely an elite city dweller, from a very high social class.

This manuscript appears to have been intended for a private individual, whilst the Divine Comedy was deemed to be a work for the educated public of Dante’s time. The work immediately garnered an extraordinary success. In addition, it contributed decisively to the consolidation of the Tuscan dialect as the Italian language. The text, of which we do not possess the autograph copy, was in fact copied in a large number of manuscript copies from the very first years of its circulation right up until the advent of printing.

Many were the historical events linked to Dante’s Divine Comedy. Please, see the extensive bibliography available.

This codex is one of the most precious and ancient manuscripts of the Divine Comedy that has come down to us, as well as one of the historic relics held by the Angelica Library.

The manuscript appears in the inventory of the library of Cardinal Domenico Passionei (1682-1761), which was acquired by the Angelica Library in 1762, after the prelate’s death.

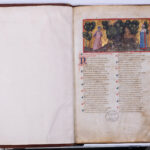

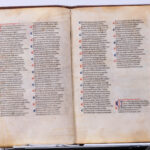

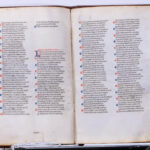

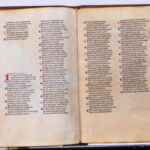

The Divine Comedy was written in the vernacular language. However, a few rare marginal notes, almost contemporary, that provided historical information on Minos, Nino, Semiramis’ husband, Cerberus, or even rhetorical arguments about similitude (f. 14r/v), which were written in Latin. Rubrics introducing the individual cantos were also written in Latin.

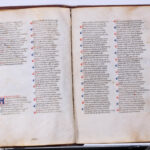

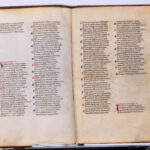

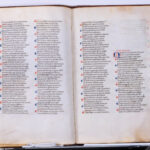

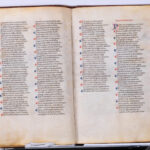

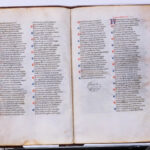

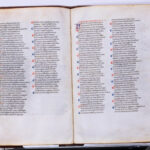

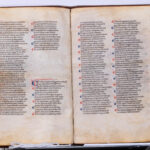

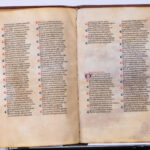

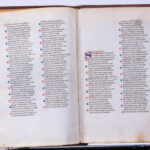

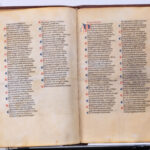

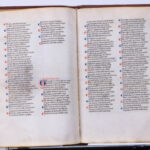

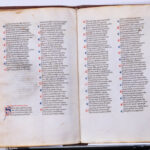

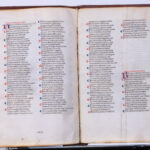

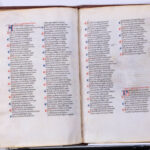

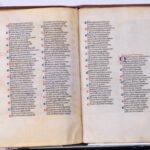

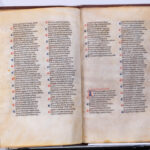

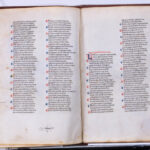

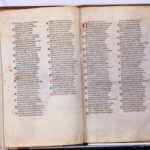

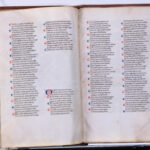

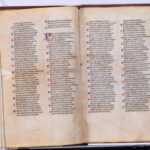

The membranous manuscript, with paper guards, comprising ff. VII + 94 + III, has the following dimensions: 345 x 240 mm (f. 65) and a modern lapis page numbering in the upper external corner of the recto of each folio. The ruling was inserted in colour. The text, set out in two columns, was transcribed by a single copyist using a professional littera bononiensis script.

According to a well-established tradition, it is likely that the manuscript was produced in the area of Emilia, more precisely in Bologna or, perhaps as a more recent study has suggested, in a Po Valley centre in close contact with the Emilian city, such as Piacenza. The proposals of the localisation of the codex, based essentially on the study of the figurative culture of the miniatures that are included in the volume, seem to be supported by palaeographic evidence and the copyist’s use of a professional littera bononiensis script.

The poem was composed to be read in sequential order.

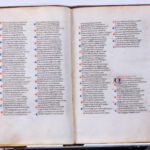

The rich iconographic programme, probably elaborated by a refined connoisseur of Dante’s opus, provided for 100 tabular miniatures, predominantly bordered in red, one for each canto of the poem, as an introduction to the opening of the canto. Among the many planned illustrations, only those for the Inferno (34) were completed. Only blank spaces intended to house the others remain.

Each illustration figuratively transposes one or more episodes from the respective canto. Except for the first, the remaining illustrations are set in a barren, mountainous landscape with a gilded background.

According to some scholars, the rich illustrations can be attributed to two miniaturists. The main miniaturist, who was the author of the proem miniature, and the second, whose hand the remaining illustrations were to have been attributed. The first miniaturist seems to be distinguished by a greater sense of monumentality in the rendering of the characters and the scene as a whole.

There are also numerous watermarked initials marking the beginning of each canto, and simple initials painted in yellow, preceded by paragraph marks in blue and red, at the opening of the tercets.

The Divine Comedy narrates Dante’s fantastic journey into the three realms of the afterlife. It is an allegorical poem, which was composed to bring people back to the path of goodness and truth by describing the punishments and rewards that await sinners and the virtuous in the hereafter. Although it was a continuation of many of the characteristic modes of medieval literature and style (religious inspiration, didactic and moral purpose, language and style based on the visual and immediate perception of things), it was profoundly innovative because, as has been noted in particular in the studies of Erich Auerbach, it tends towards a broad and dramatic representation of reality.

Dante, in his Divine Comedy, encounters many historically documented personages of his era. They belonged to the realms of politics, the Church, and the arts. His narrative reconstructed the emblematic actions, the context, the place and the atmosphere for each person. He then encountered groups, crowds, hosts of souls, monsters, demons, and angels.

The canonical procedure for writing that was generally followed was as follows:

- The support was selected and prepared, in the case of the MS 1102, in parchment.

- The quire was constructed (4, 5 or 6 leaves folded and tucked inside of one another).

- The preparatory perforation was carried out.

- The ruling was then done, either dry or with coloured lead, according to a full-page or 2-column scheme. The MS 1102 has a full-page scheme and the ruling was inserted dry.

- The work was copied, leaving space for initials and headings (i.e. accessory texts such as titles, contents, and the explicit).

- The parts in red were then inserted, i.e. the headings and any pen strokes on the capital letters (it was almost always the copyist himself who would do this).

- The miniaturist would draw in the initials, which could also extend into the margins.

- The illustrations could have been inserted into the spaces specifically reserved for the script. Or, if they occupied an entire page, this could be part of the quire, or the illustration could be executed on a single folio that was then inserted inside the quire. In this second case, when observing the structure of the quire, one would notice an oversized folio with half missing.

- Last, the quires were first sewn together and then sewn onto to the cover. This operation could have also taken place over a period of time.

We are not aware of the specific execution technique used in MS 1102.

The canonical procedure for the execution of a miniature prescribed that on the parchment that had been well-stretched and cleaned, the preparation would be laid out and the basic preparatory drawing would be made.

So, one of the possible preparations for gilding, was Armenian clay, otherwise known as “bole” mixed with glue, until a perfectly homogenous base was obtained on which to apply gold leaf gilding. The colour of the bole will influence the tone of the gilding to be applied. So, a red or a yellow bole could be used if a warmer or paler tone was desired respectively. This layer of clay would be applied with a soft brush. Very fine gold leaves would then be applied to the bole. The gold leaf would then be burnished with agate stone until it was gleaming. Gilding could also be applied with a brush.

Then finally, the colours with which the backgrounds and figures were to be painted would be prepared. Once the main shapes and figures were composed, other decorations and ornaments could be drawn: the rinceaux in the margins and the ornate initials, and then the historiated initials. The order of execution of these elements could vary. These ornaments are partially present in MS 1102. The miniature would first be left to dry and in the end it would be transferred to the person who was to assemble the quire.

We note the extensive use of the folio, which was then employed in all the miniatures used to decorate the background.

On the recto of the last page, long after the transcription of the Commedia had ended, there was transcribed a passage from the Alexandreis, a heroic poem, dedicated to a great personality who was also the protagonist of an extraordinary journey, also composed in late medieval times, though in Latin.

This manuscript was restored by the Paolo Crisostomi Studio in 2008.

Although it shows signs of previous bacterial attack and mechanical abrasions of some of the illuminated figures, the manuscript is actually in a good state of preservation.

- As part of the Codex 4D project, thermographic and reflectographic surveys were conducted in the mid-IR (spectral range 3-5 µm). These are imaging techniques that allow structural and/or subsurface elements of both the ligatures and the miniatures to be visualised.

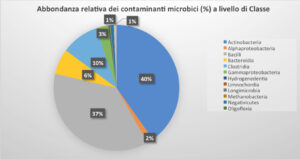

Microbiological samples were also taken on the spine and on folio 50, and then were analysed in the laboratory with Sanger sequencing. As in all documents analysed with molecular techniques, actinobacteria was found to be among the prevalent contaminants (Micrococcus sf. was also isolated from f. 50), followed by Bacilli, environmental saprophytes (Staphylococcus was also isolated from the spine), and then at low incidence there was found Clostridia, Bacteroidia and other contaminants due to handling by users or present in the air of the Library, since they were detected in other volumes analysed as well.

HPLC and FTIR spectroscopy chemical analyses were conducted on ff. 4v-5r and ff. 55v-56r to investigate possible degradation material on the parchment (see annotations in the virtual model).

For the Divine Comedy, reflectographs in the mid-IR were used to align RGB images with thermographic images so that a 3D representation in the IR could be obtained. Thermography was used to study some of the miniatures. This method revealed some useful information on the state of adhesion of the gilding (no sub-surface detachments extending from small gaps were visible. The miniatures were found to be in an excellent state of preservation). Both techniques showed some elements of the preparatory drawing with greater contrast and allowed the recovery of lost portions of the decoration. The thermographic surveys carried out on folio 4r showed some iconographic elements of the figure of Minos, guardian of the II circle, which would appear to have been intentionally damaged together with other figures of the guardians of the circles. Instead, the thermographic investigations on folio 56v returned a map of the extent of the biological damage (violet spots).

Reflectograms in the mid-IR provided some indications of the nature of the inks, showing a higher concentration of carbon in the ink used on folio 56v.

As far as microbiological investigations are concerned, the isolates identified by Sanger sequencing were gram positive bacteria belonging to the actinobacteria, common inhabitants on the skin of mammals or in soil.

The extremely low number of contaminants and their habitats suggest that these microorganisms were most likely due to user handling or they were present in the air of the library, given the volume’s excellent state of preservation.

For the rich bibliography, please refer to MANUS onLine.

Add to this the most recent:

- L. DI CARLO, N. CANNATA, M. SIGNORINI, Scheda di catalogo n°. 8, Roma, Biblioteca Angelica, ms. 1102 (S.2.10), in La ricezione della Commedia dai manoscritti ai media (Roma, Palazzo Corsini, Biblioteca dell'Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei e Corsiniana, 26 marzo 2022 - 25 giugno 2022), Catalogo della Mostra a cura di R. ANTONELLI, S. DE SANTIS, L. FORMISANO, Roma 2022, pp. 51-52 (con riferimenti

Noemi Orazi, Fulvio Mercuri, Cristina Cicero,* , Giovanni Caruso, Ugo Zammit Sofia Ceccarelli and Stefano Paoloni The “Lost Guardians” of Dante’s Inferno: Medium Wave Infrared Imaging Investigations of a XIV Century Illuminated Manuscript. Heritage 2022, 5, 991–1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5020054